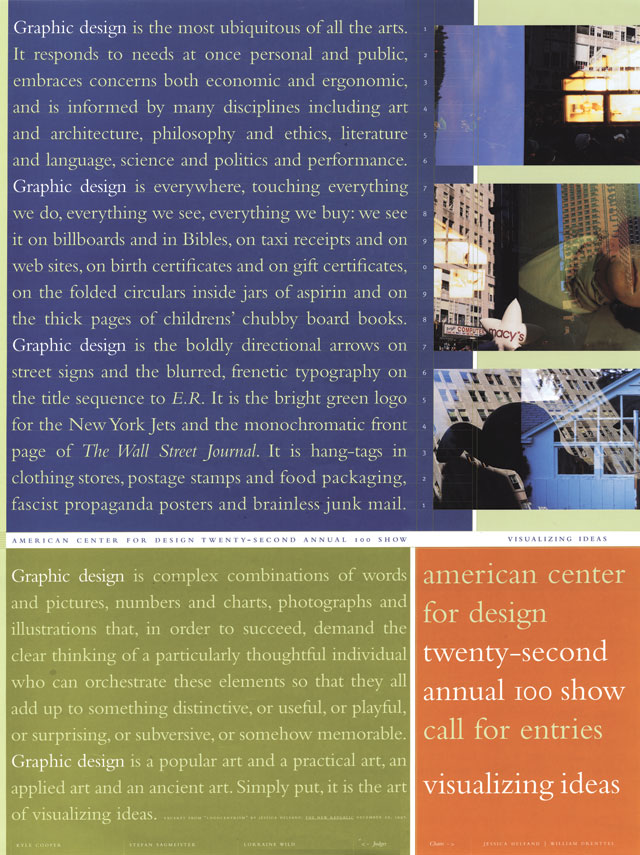

2013 AIGA Medalist: William Drenttel and Jessica Helfand

Recognition

2013 AIGA Medal

Born

1953, Minneapolis, Minnesota (William Drenttel)

1960, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Jessica Helfand)

By Michael Bierut

September 2, 2013

Designer, theorist and publisher William Drenttel is recognized for advancing critical thinking about design; for his long-standing commitment to integrating design strategy into organizations; for expanding design’s role in social innovation; and for his work as cofounder, editor and publisher of Design Observer.

Designer, educator and writer Jessica Helfand is recognized as an incisive critic; a pioneer in design practice and education; an innovator of new forms of visual narrative; and for her work as cofounder of Design Observer.

This is not a simple story, but it has a simple lesson. Theirs was destined to be a partnership as consequential in its way as some of the most storied in the design profession: think of Charles and Ray Eames, say, or Massimo and Lella Vignelli. But it took a while to happen.

William Drenttel was born in 1953 in Minnesota, though his family moved to Southern California a year later. He grew up about ten miles from Disneyland. To this day, Drenttel’s demeanor seems to combine the rectitude of an upper Midwesterner with the laid-back attitude of a Los Angeleno. He attended Princeton University, spending a year studying in Paris, and graduated in 1977.

Jessica Helfand was born in 1960, and moved from Philadelphia to Paris with her family when she was 10, where she lived for nearly five years. It so happens that Drenttel spent his year abroad at the same time, not that far away, but they never met. Helfand returned home and attended Yale University, studying graphic design and architectural theory. After graduation, she took a job writing soap operas for Procter & Gamble, eventually becoming a junior scriptwriter on CBS’s Guiding Light. She credits this experience with sparking her interest in the role of narrative within design.

Thomas Miller, “Dr. Margaret T. G. Burroughs,” 1995. DuSable Museum of African American History, Chicago. Photograph: Chris Dingwall.

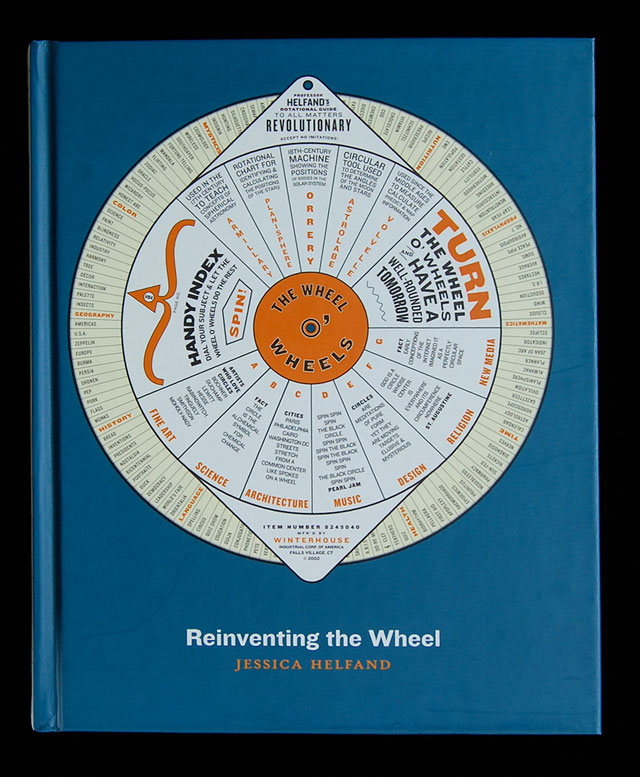

Reinventing the Wheel, 2002 Publishers: Princeton Architectural Press and Winterhouse Editions; Author: Jessica Helfand; Art director: William Drenttel; Designers: Kevin Smith, Rob Giampietro.

Photograph of Fred Ota, Tom Miller, John Weber, 1953. Thomas H. E. Miller Design Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Drenttel, meanwhile, got a job as an assistant account executive at Compton Advertising. His main client was Procter & Gamble. In the early 1980s, Drenttel and Helfand worked in the same building, two floors apart—but still they never met.

Drenttel, promoted to senior vice president, became a consummate pitchman, crisscrossing the world and winning accounts with an ease that, eventually, would begin to disgust him. (“I actually came to hate advertising,” he wrote much later.) In the midst of this, Drenttel was becoming increasingly fascinated by design. Charged with improving the stores of a national fast-food chain, he brought in the hottest designers in town, a small but soon-to-be-legendary studio, M&Co, led by Tibor Kalman and the firm’s art director, Stephen Doyle. Drenttel and Doyle became friends, and one day the idea of going into business together came up. “It was an off-the-wall idea we both jumped on,” Drenttel later told the New York Times. They quit their respective jobs and Drenttel Doyle Partners was incorporated two weeks later. It was 1985.

After three years of scriptwriting, Helfand realized that she wasn’t made for soap operas; she had studied design and architectural theory, after all. Through a family connection, she got a $10-an-hour job at a small studio in midtown Manhattan. She was the only employee. Her boss was demanding, scrutinizing her projects and sending her away each time with the command, “Move it up a hair.” Eventually, after receiving this input once again, she would simply leave the room and wait, as she later wrote, “for what I believed to be the requisite amount of time anyone would require to actually make the ‘move it up a hair’ adjustment.” Then she would return and the work would inevitably be approved. After 18 months of this, Helfand was accepted into the M.F.A. graphic-design program at Yale and left for New Haven to study with Paul Rand, Bradbury Thompson and Armin Hofmann.

Back in New York, if Drenttel Doyle Partners wasn’t an overnight success, it was the closest thing possible. Within a year, the firm created the design for Spy, a satirical monthly magazine with a tiny budget and an approach to page layout that was widely copied and continues to be enormously influential more than 25 years later. Freed from restraint, Drenttel and Doyle were eager to define a new kind of studio, practicing a hybrid of design, advertising, marketing and publishing that eluded quick definition. They redesigned The New Republic, repositioned the Cooper-Hewitt Museum as the National Design Museum and helped launch the biggest real estate development in town, the World Financial Center, with a series of print ads that featured text from prominent poets and writers like Dana Gioia and David Rieff.

William Drenttel and Jessica Helfand (Photo: Bojan Velikonja).

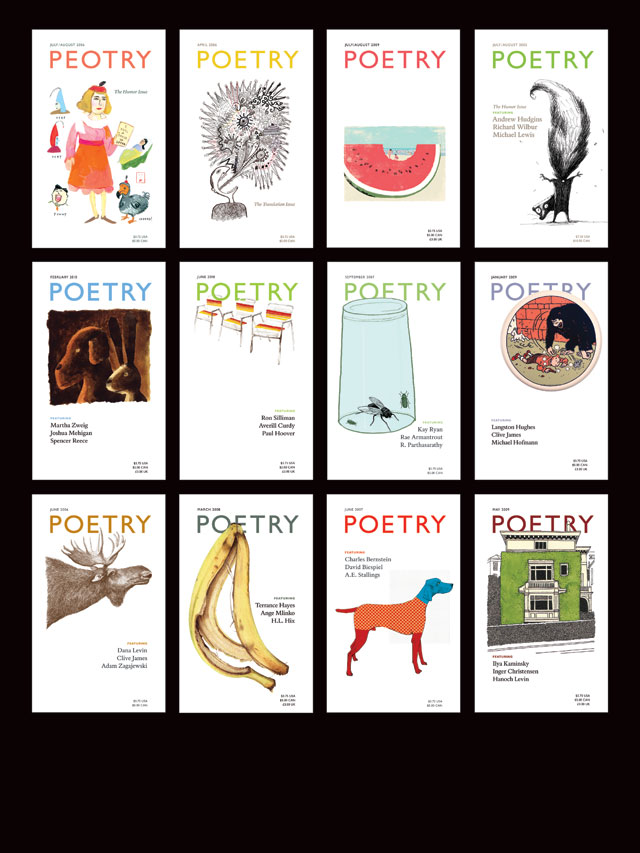

Assorted covers for Poetry Magazine, 2005–present Design directors: Jessica Helfand and William Drenttel; Art director: Alex Knowlton; Illustrators: Various.

Design Observer, 2003–present Founding editors: Jessica Helfand, William Drenttel, Michael Bierut, Rick Poynor; Publisher and editorial director: William Drenttel; Design director: Jessica Helfand; Designers: William Drenttel, Michael Bierut, Betsy Vardell.

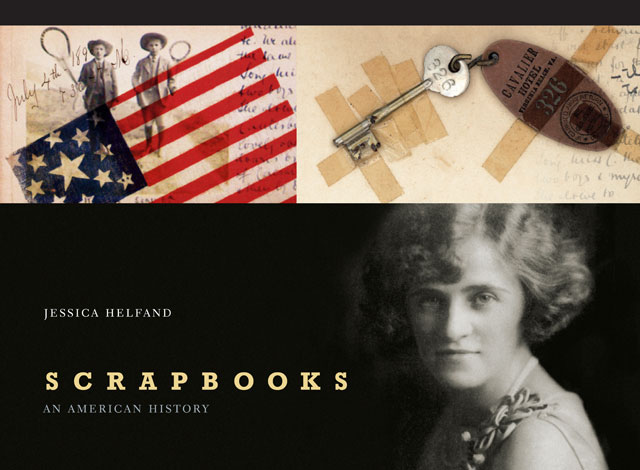

Scrapbooks: An American History, 2008 Publisher: Yale University Press; Author: Jessica Helfand; Design director: Jessica Helfand; Designers: Jessica Helfand and Teddy Blanks.

Helfand completed graduate school in 1989 and became a magazine designer. Here was a place to reconcile her passion for storytelling with her studies. She returned to Philadelphia as design director for the Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine. This was a moment when the digital revolution was arriving, and one of its first beachheads was publishing. Many of her colleagues viewed this strange new world with alarm. Helfand was fascinated by it.

If you could create narratives for the television screen, why not the computer screen? “Are we makers or managers? Controllers or curators? Editors or aesthetes?” she would later write. “To what degree do the classic principles of design…apply in an environment characterized by randomness and reciprocity, distribution across networks and democracy among netizens?” Well before the end of the 20th century, Helfand placed herself squarely in the middle of a debate that still continues. She became a media columnist for Eye magazine, and her writing there would become the heart of her first book, Screen: Essays on Graphic Design, New Media, and Visual Culture, published by Princeton Architectural Press in 2001.

Her interest in the changing profession took her to an AIGA conference in Miami in 1993. It was unusually bleak and rainy, but there was at least one ray of light: it was here that Helfand and Drenttel finally got to know each other. Helfand was guest editing an issue of the AIGA Journal of Graphic Design and, upon returning to Philadelphia after the conference, called to ask if he was free for lunch to talk about story ideas. “No,” he replied (“pretty quickly,” according to Helfand). “But I’m free for dinner.” They became friends, and then more, and in 1997 they became business partners.

It was clear from the start this partnership would be different. Drenttel and Helfand had experienced the scale of the international ad agency, the hot New York design firm, the bustling urban newspaper. In their new venture, they deliberately took the opposite direction. Their partnership would be just the two of them and a few helpers. Within a year, they moved to the remote town of Falls Village, Connecticut, where they had discovered a place they could live and work, the modernist 1932 painting studio of Radio City Music Hall muralist Ezra Winter. It was the studio that gave their business its name: Winterhouse.

Winterhouse, deliberately, has followed no recognizable model. Yet the firm’s output has been prodigious. Winterhouse Studio is a design firm, and in that capacity Drenttel and Helfand have redesigned magazines like Poetry and the New England Journal of Medicine, created identities for the filmmaker Errol Morris and the Yale School of Management, and designed websites for The New Yorker, Nextbook, The Paris Review and the NYU School of Journalism. But studio work for clients—even at this high level—comprises only part of their work.

As Winterhouse Editions, the firm co-publishes limited and trade editions of works by Thomas Bernhard, Paul Auster, Franz Kafka and others. In addition to Screen, Helfand has written and designed two additional landmark books: Reinventing the Wheel (2002) and Scrapbooks: An American History (2008). Each volume is, as expected, elegantly designed and impeccably produced. Not so expected? Learning that the National Security Act of 1947 required the Bush administration to prepare a comprehensive strategy statement for Congress. Believing that the document deserved greater attention, Drenttel published and distributed it on the eve of the Iraq War in 2002. It, too, was elegantly designed and impeccably produced.

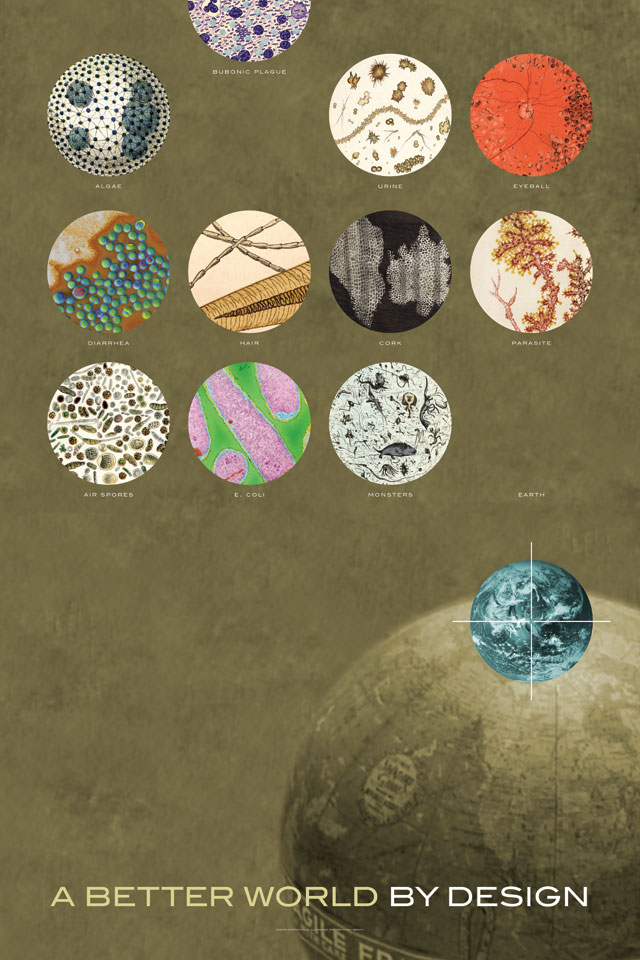

This impulse—not to wait for client work, but to respond with design when confronted with real-world needs—led Drenttel and Helfand to found Winterhouse Institute in 2006. The Institute’s initiatives include the AIGA Winterhouse Awards for Design Writing & Criticism; the Polling Place Photo Project, which documented citizen experiences at poll sites during the 2006 and 2008 elections; the development of comprehensive case studies on design and social enterprise with the Yale School of Management; and the creation of conferences on the power of design for social change on behalf of the Rockefeller Foundation, the Aspen Design Summit and the Mayo Clinic.

In the midst of this activity, Drenttel has been national president of AIGA, co-edited the Looking Closer anthologies of design writing and taught design thinking and creative strategy at the Yale School of Management. Helfand has served on the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee, as a guest artist at Wesleyan University and as senior critic at the Yale School of Art and lecturer at Yale College. Together, they were the first recipients of the Henry Wolf Residency at the American Academy in Rome. And they are parents to two children.

But perhaps Drenttel and Helfand’s broadest impact on the profession has been felt through their website for design, visual thinking and cultural criticism, Design Observer. It started in 2003 as an experiment with two other friends. Ten years later, the site has hosted more than 600 writers who have written more than 4,800 articles to date, with more than 183,000 unique monthly visitors. According to 2010 AIGA Medalist John Maeda, “Design Observer has shown the world how design can be fluently communicated through fresh words, instead of design.”

It is through this project that I really got to know William Drenttel and Jessica Helfand; with Rick Poynor, we were the site’s four original founders. And it was through this experience that I learned their secret. When they started Design Observer, Drenttel and Helfand didn’t have a business plan. There were no agreements to sign, no contracts to send on to lawyers. There weren’t any planning meetings with whiteboards and Post-it notes. There was nothing more than a simple offer: let’s do this, let’s see what happens and let’s keep doing it as long as it’s fun. “The minute it stops being fun, we’ll just quit,” Drenttel once said.

This is what Drenttel and Helfand have taught us. Their individual histories, so deep and expansive, have given them imagination. Their experiences in the world of culture and commerce, where they learned what they wanted to do and what they didn’t want to do, have given them conviction. Their trust in their audiences, in their collaborators and, most of all, in each other has given them optimism. All of these things have brought these two designers to a place in their lives where making great, important design can seem like the simplest thing in the world. And this is their lesson: you can just keep doing it as long as it’s fun. And if you’re lucky, it always will be.