Recognition

2008 AIGA Medal

Born

1915, Memphis, Tennessee

Deceased

2007, Chicago, Illinois

By Lauren Weinberg

September 1, 2008

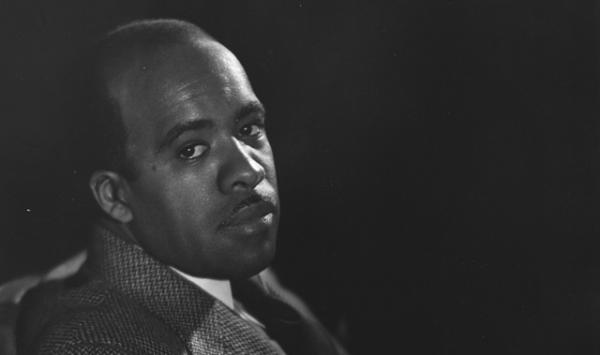

It took LeRoy Winbush 11 years to become the first black member of the Art Directors Club of Chicago, but once the organization accepted him, only five years to become its president. “Winbush was a great motivator for designers of color,” says AIGA national board member Vernon Lockhart, who considered Winbush his mentor. Lockhart adds, “He would tell me, 'You have to get to the table where the decisions are being made. The way to change something is to be active in it instead of complaining on the sidelines.'”

Winbush moved to Chicago from Detroit as a teenager and became a graphic designer there in 1936, one week after he graduated from high school. At the time, the profession had only a few black practitioners, one of whom—Charles Dawson—had numerous clients on Chicago's South Side. Winbush started out in the same community, but his role models were South Side sign painters. He jumped from an apprenticeship in a sign shop to a job designing signage, murals and flyers for the Regal Theater, where he “rubbed shoulders” with performers such as Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, according to Lockhart. Music was an important influence on Winbush's career as well as a beloved hobby: as a teenager, he performed at Chicago's Century of Progress exposition with his band the Melody Mixers, and he later designed album covers for the Ramsey Lewis Trio and other groups signed to Mercury Records.

Yet unlike Dawson, Winbush worked for a diverse range of clients at a time when racism seemed to be an insurmountable barrier. After leaving the Regal Theater, he joined the sign shop at Goldblatt's, a local department store chain where he was the only black employee. By the time he left seven years later, he was the art director for all the Goldblatt's stores, creating merchandising displays and managing a staff of 60 people. He had also become an accomplished airbrush illustrator. Winbush founded his own firm, Winbush Associates (later Winbush Design), on the South Side in 1945. Every morning, he spent three hours working as the art director for the Consolidated Manufacturing Company. Every afternoon, he spent three hours working as the art director for Johnson Publishing, designing layouts for magazines including Ebony and Jet. During this period, Winbush served as the president of the renowned South Side Community Art Center as well. “Because of the Great Migration, Chicago had a set of black institutions that you did not have in any other city in the United States,” notes design historian Victor Margolin. Winbush's opportunities at thriving local enterprises like the Regal Theater and Johnson Publishing helped him build a strong support network in Chicago's black community. To win clients outside it, he had to rely on his own ambition—and what Lockhart describes as “charisma” combined with a willingness to learn.

(from top) Identity designs for Office Suites, Inc., and 1968 Illinois Sesquicentennial..

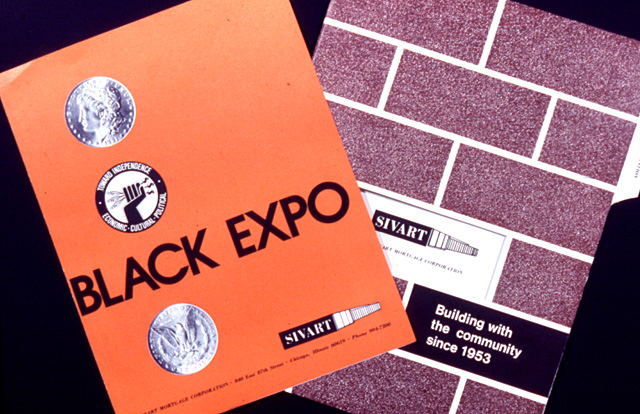

Branding materials for the Black Expo, at one time the largest gathering of black businessmen in history.

(clockwise from top left) Album cover designs: The Staple Singers' Will the Circle Be Unbroken; The Ramsey Lewis Trio's Country Meets the Blues; The Swan Silvertones' Singing in My Soul; and Ramsey Lewis and His Gentle Men of Swing.

A self-portrait in the December 1955 ADC Chicago News Bulletin illustrates how busy the multitasking designer must have been: the photomontage depicts Winbush with six arms sprouting from his well-tailored suit, the better to hold his camera, hammer, T-square, paintbrushes and other implements. Margolin suggests that this illustrates how Winbush “couldn't just be one guy; he had to be five guys at once.” His diligence paid off. “LeRoy was a pioneer in establishing a business model for black designers,” states Margolin, who notes that while some of Winbush's peers were literally forced to “work behind a screen, he was out there as a black entrepreneur.”

A 1958 Ebony article profiling Winbush—entitled “The Barnum of Bankers Row”—indicates how successful his business model was. Winbush “excelled at exhibit design,” according to Margolin, and he convinced a bank in the heart of Chicago's financial district to hire him to create window displays. Such things were unheard of in banking at the time, but Winbush Associates soon cornered the market its principal had invented, devising elaborate narrative displays with mannequins and props for 62 clients in the financial industry. When enthusiasm for this form of advertising waned among the banks, Winbush found other outlets for his expertise in exhibit design. In 1959, he served as chairman of exhibits for the International Design Conference at Aspen, which he was closely involved with for eight years. Winbush also helped design Illinois's exhibit at the 1964 New York World's Fair—including its animatronic Abraham Lincoln, which was the prototype for the figures in the Hall of Presidents at Disney World.

A few years later, Winbush began teaching visual communications at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and typography at Columbia College Chicago. This was an impressive feat for someone who had never received any formal design training. (In a 1988 interview with SAIC professor Frank DeBose, conducted for the Archives of American Art/Smithsonian Institution Oral History project, Winbush admitted that after high school, he had wanted to attend the SAIC so badly that he sat outside it for hours, but he lacked the money for tuition.) At the same time, he mastered a new personal skill—scuba diving—having finally learned to swim in his late 40s. In 1985, when he was almost 70, Winbush was part of the underwater crew that built the coral reef for the Living Seas pavilion at Epcot Center, and he celebrated the start of each new year by diving into icy Lake Michigan for more than a decade afterward.

Although Winbush insisted that he wanted to be known as a “good designer,” not a “black designer,” he “believed he could use design as a tool to help the black community,” says Lockhart. He developed a long-term exhibition about sickle-cell anemia for the city's Museum of Science and Industry and in 1990 became an exhibition consultant to the DuSable Museum of African-American History, the first museum of its kind. Winbush continued designing exhibitions for the DuSable on subjects such as the Underground Railroad and the uprising on the slave ship Amistad until he was well into his 80s.

Lockhart sees these achievements as evidence of the same determination that enabled Winbush to overcome whatever prejudice he encountered. In his interview with DeBose, Winbush acknowledged that he might not have been the only black designer fighting for unequivocal acceptance, “but I didn't know of too many others. Every place I went I was by myself.” He told DeBose that he joined the ADC and the Society of Typographic Arts largely to “open the door” for other black designers.

“He was a real pioneer for my generation,” Lockhart concludes. “Seeing Winbush let us know that a career in design was possible.”