Recognition

2007 AIGA Medal

Born

1938, Detroit, Michigan

By Vince Carducci

September 7, 2007

In response to F. Scott Fitzgerald's declaration that in American lives there are no second acts, memoirist Frank McCourt writes: “He simply did not live long enough.” Like the author of Angela's Ashes, who followed a high-school teaching career by winning the Pulitzer Prize and international fame, Ed Fella's second act has been more noteworthy than his first. After three decades as a successful commercial artist, Fella, at age 47, entered the MFA program at Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1985, opening the door for him to be recognized as a pioneer of postmodern graphic design. From his subsequent position as a professor at California Institute of the Arts, where he has profoundly impacted the design program for the past 20 years, Fella has since presided as vanguard master to a new generation of graphic designers.

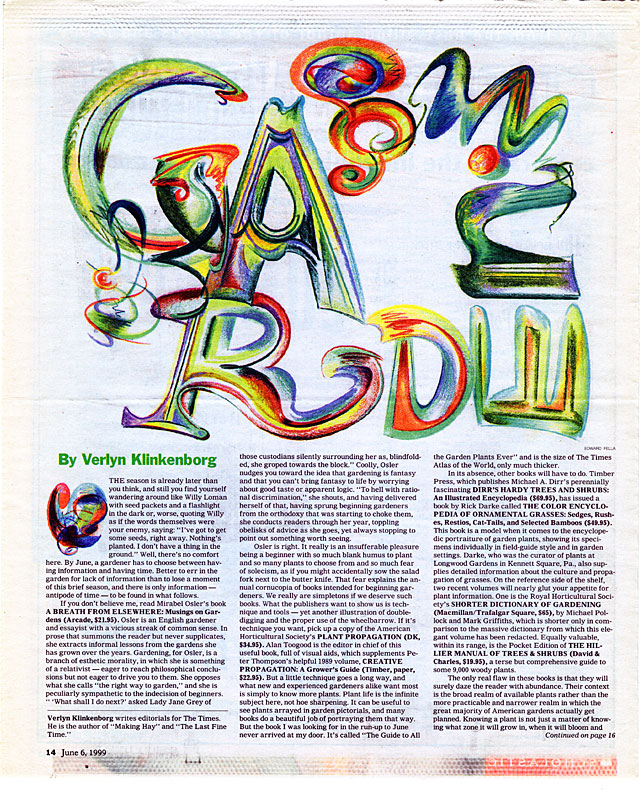

Over the years, Fella has created a body of work that's as compelling as it is unique. Prodigiously mashing up low-culture sources with high-culture erudition, Fella's work—perhaps more than that of any other contemporary designer—makes visible the postmodern concept of deconstruction, which recognizes that behind every articulated meaning is a host of other, usually repressed meanings, some antithetical. By battering and mixing fonts, engaging in visual puns and generally violating the tenets of “good design,” Fella lets a thousand flowers bloom. His designs don't cut through the clutter—they revel in it.

“Ed's work marks a sea change in graphic design,” says Lorraine Wild, a 2006 AIGA medalist. “He introduced ambivalence and ambiguity, the multiple meanings of design as text and subtext, and that graphic designers are really artists.”

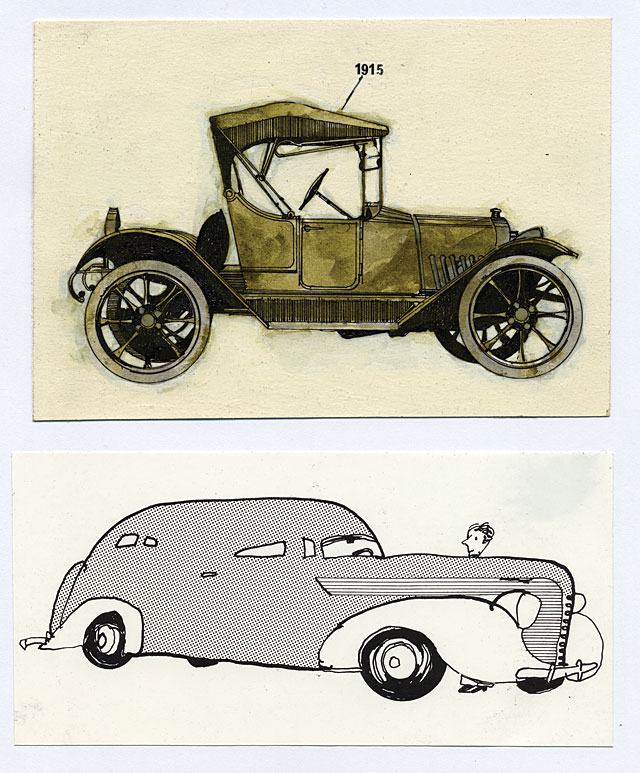

Top: The Chevy Story, 1965; below: Motor Trend Magazine, 1972.

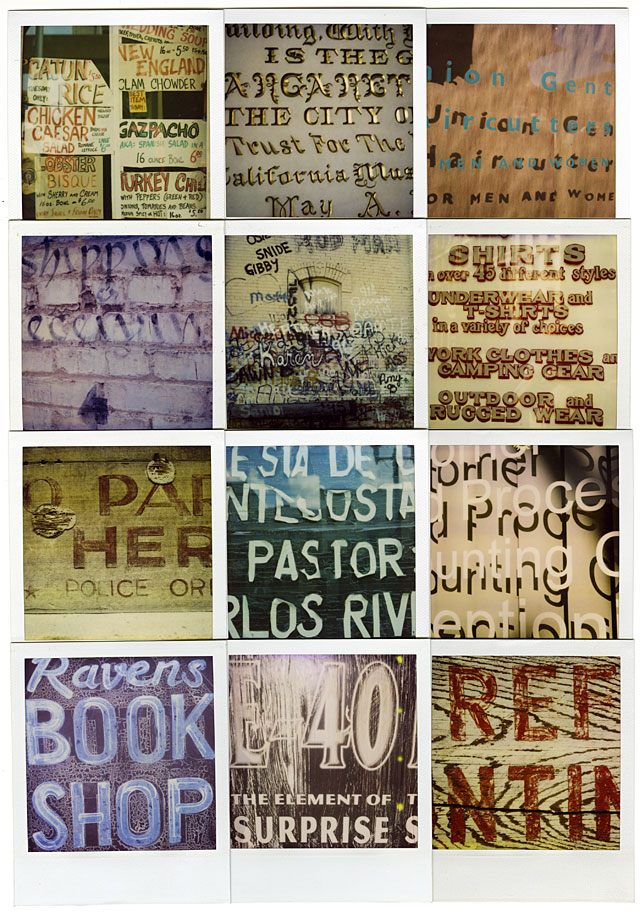

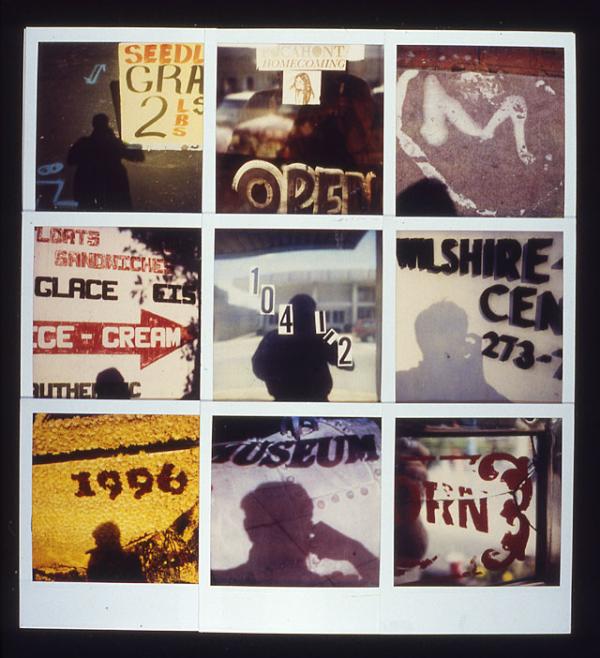

Polaroid photographs of vernacular lettering, 1990 to 2005.

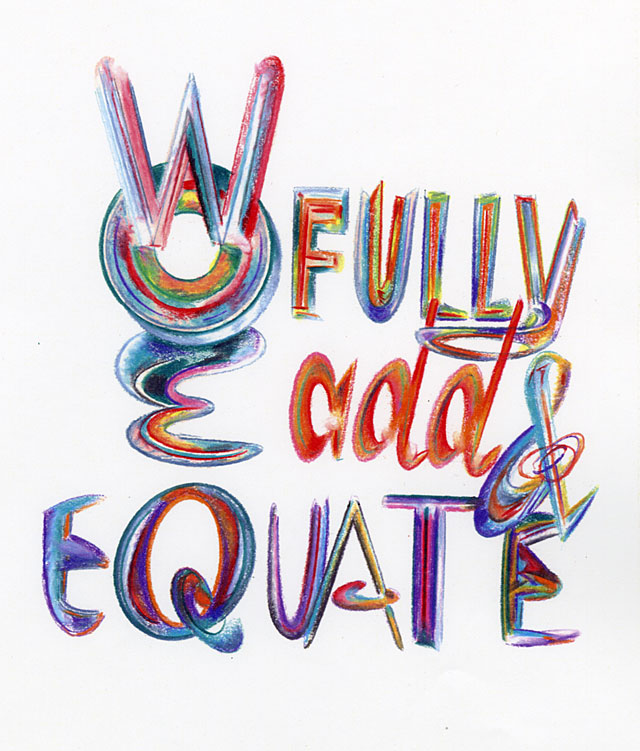

Lettering for New York Times book review, 1999 (Art direction: Steven Heller).

On the surface, there is little in Fella's background to suggest he would become one of the most influential designers of the last quarter century. Born into a working-class family in Detroit, he attended the local magnet school, Cass Technical High School, where he studied lettering, illustration, paste-up and other commercial-art techniques. After graduating in 1957, he went straight to work as an apprentice at a small firm that provided studio services to the Motor City's vibrant, though hardly adventurous, advertising industry. Fella worked steadily into the mid-1980s, freelancing primarily for automotive and health-care clients. His pieces were included in design annuals here and there. Of his commercial career, he's frequently quoted as saying, “I was the vernacular.”

Yet behind the portfolio of advertising hackwork was a creative spirit that ultimately came to the fore. From the beginning, Fella read voraciously. As a young adult he took night classes on modern literature and other intellectual subjects. He collected all kinds of music as well as pop-culture ephemera. He was (and still is) a prolific photographer. He subscribed to numerous magazines of art and culture. “He had a curiosity about everything,” says Nelson Greer, a design instructor at College for Creative Studies in Detroit who worked with Fella in the 1960s and '70s.

Even his high-school-level education, which eventually limited his career path, set the stage for later development. “Cass Tech taught the Bauhaus foundation method, where the art schools at the time in Detroit were steeped in the Beaux Arts,” Fella says. “So I actually got a more advanced education in high school than I would have had I gone to college at that point.” One of those lessons was the Bauhaus credo of eliminating the line between the so-called fine and applied arts.

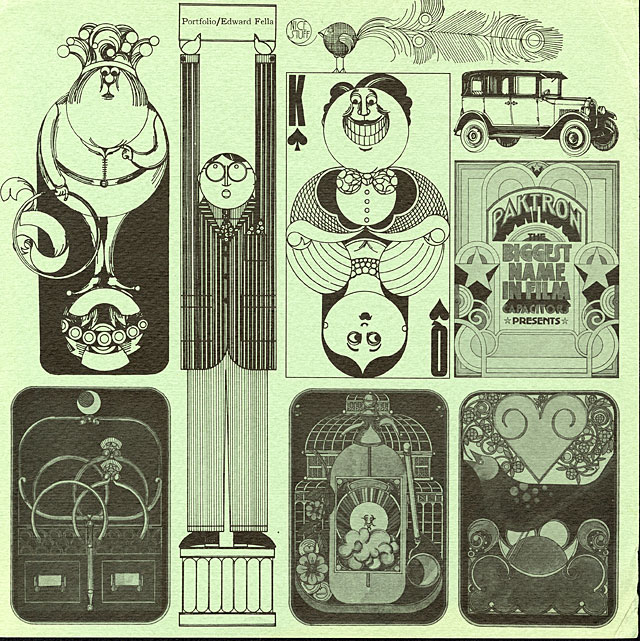

The work for which Fella is now known has its roots in his freelance days. Like other freelancers in between assignments, Fella created samples of different techniques as part of soliciting clients. Coupling mechanically reproduced material with considerable drawing and lettering skills, Fella created intricate and often whimsical collages for his portfolio. Photocopiers, which had become office fixtures, expanded the possibilities for imagery and composition. Many of these early pieces feature enigmatic messages, a result of incorporating leftover bits of type into the design in a parody of the “greeking” used in font books and in comprehensive layouts. Experimental personal work soon became his true passion.

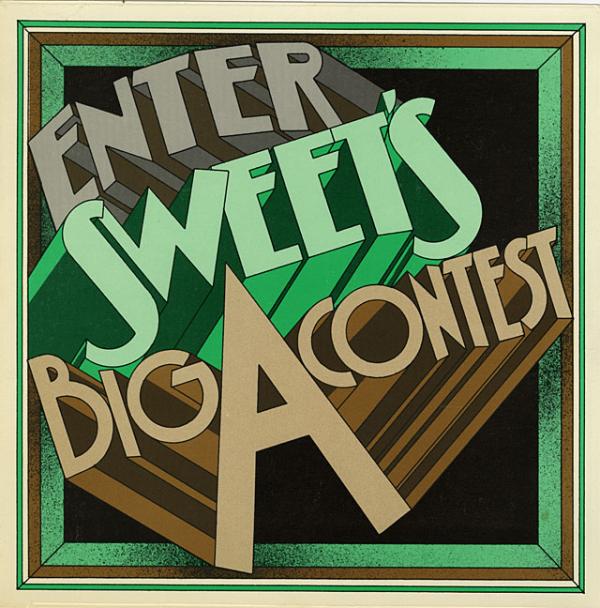

Sweets catalogue promotion, mid-1970s.

Sketch book page, 2005.

Edward Fella: Letters on America (Princeton Architectural Press, 2000).

Illustration sample sheet, 1968.

It was during this period in the early 1970s that the planets aligned and Fella met the two people who would become instrumental in his move toward becoming an “exit-level designer,” his favored term. At Designers and Partners in downtown Detroit, the lives of Katherine McCoy, Lorraine Wild and Fella intersected. McCoy, a 1999 AIGA medalist, recalls how he shaped his situation at the bustling agency. “Ed in effect conducted a daily symposium at lunch, in the break room and after hours in the bar downstairs,” she says. “We all learned an incredible amount.” Wild, who joined as an intern in 1973, notes that while many designers in the studio talked about design and avidly collected it, Fella was the only one making new work: “Ed was already sophisticated before he went to Cranbrook.”

Just how innovative was his work? Even before Adobe had figured out how to kern digital fonts, Fella was deconstructing lines of copy, modifying typefaces (turning Bembo into Bimbo by hacking off the serifs, to cite one example) and jumbling them up. Not for another decade would desktop publishing achieve anywhere near the eye-bending effects Fella was getting with copy-camera photostats and X-Acto knives. McCoy, who left Designers and Partners in 1971 to head up Cranbrook's design department with her husband Michael, an industrial designer, invited Fella to present his work to her students and offer critiques over a decade before he enrolled there in the master's program. “If anyone is meant to be a student and teacher in a rigorous educational environment, it's Ed Fella. He was a powerful influence on our students,” she says.

The burgeoning alternative arts scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s provided an ideal venue for Fella to take his work from the private sphere into the public domain. The posters, catalogs and other collateral he made for various nonprofit arts organizations—especially Detroit Focus Gallery—cemented Fella's reputation, and to this day form the foundation for his more recent work. Ironically, the presumably more sophisticated art world hasn't always appreciated Fella's groundbreaking designs—in fact, many of the artists whose shows he “promoted” have been among his most vociferous critics. Fella may have the last word, since those lesser known artists don't have their work in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, but he does.